The Eastern Emirates Charity Ball is the most important night of Pranav’s year. Moments from now, a hundred of the Gulf’s wealthiest westerners will descend on the ballroom of the Arabia Grande Hotel. The fact that he turns thirty today—his tenth birthday on foreign soil—should be the last thing on his mind, considering.

But he’s not worried. A full decade, now, of nights in the dusky lounge, lighting cigars for the emirs and the oil expats. A lifetime of afternoons, too, sweated out on the veranda. He’s served brunch to princesses and brandy to naval commanders.

He knows, in other words, how to disappear in plain sight.

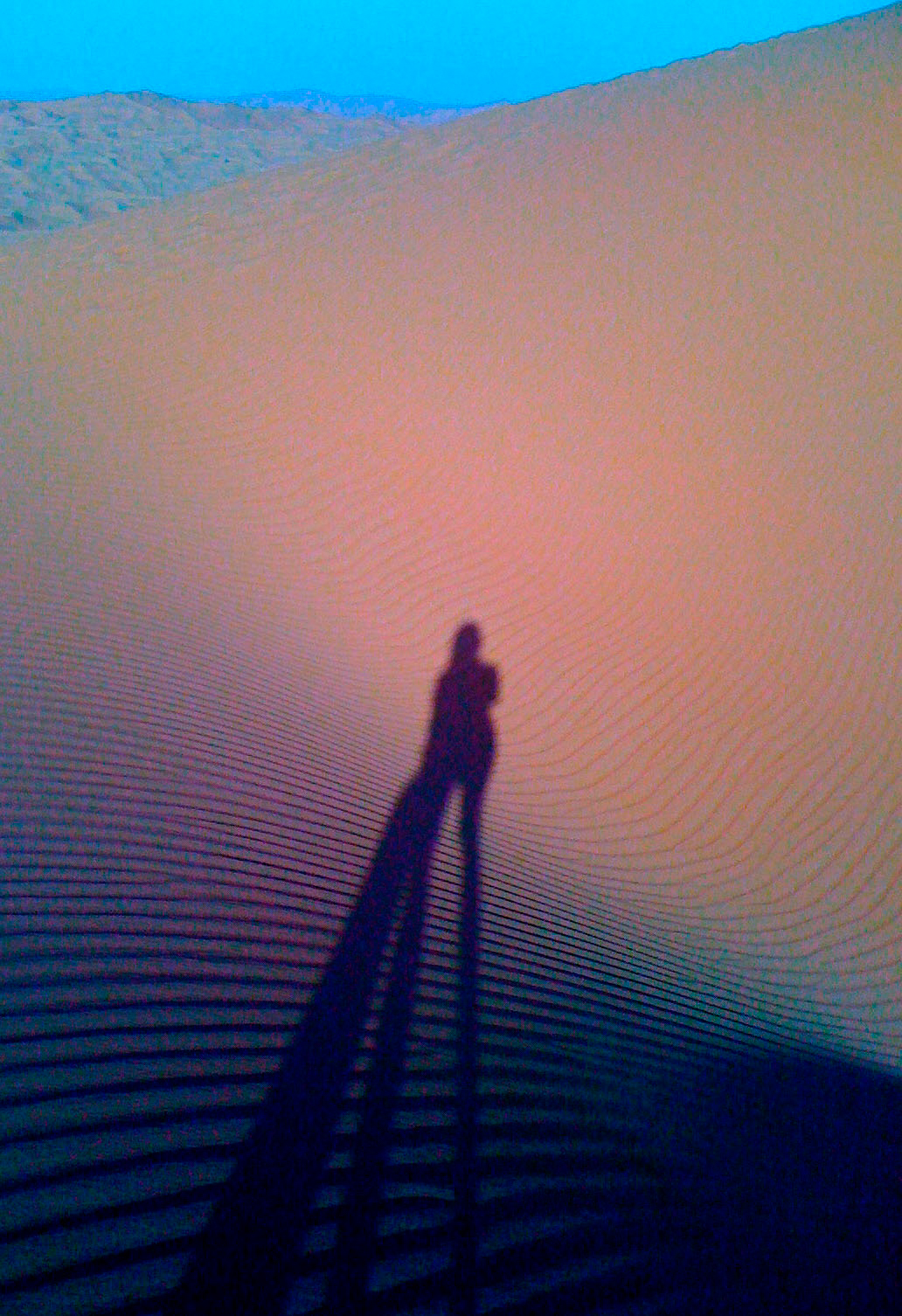

The trick is to think of yourself as a shadow, or a ghost. Glide in to replace the fallen fork before it’s missed, top up the madam’s champagne. Catch the tuxedo jacket tossed your way as the band kicks up and the dance floor fills. Then, at the end of the evening, float onto the edge of their blurred vision. Catch their eye and duck your head, demure, like a virgin betrothed. A wallet will open, or a beaded clutch: another fifty, sixty riyals to send back home. Half a week’s wages, there in your hand. A reward for making yourself invisible.

The hallway between the lounge and ballroom is long and bright and lined with floor-to-ceiling mirrors; here he stops for a moment, as he does every year, to inspect the evening’s uniform. Burgundy shirt, burgundy vest, black slacks: everything brand new, designed and sewn for a single night. He fingers a crooked pleat and—can’t help it—thinks of his father. Even with his eyesight failing and no one to help, the old man could make better uniforms—and probably for less. Does Rami, the old Pakistani event supervisor, know who contracts the Charity Ball uniforms? And if he does, would he share the information? Maybe if—

But he’s wondered these things before and it’s pointless thinking, a distraction worse than brooding over a birthday. He straightens the bow tie, pats his pockets, and pushes through the double doors to the ballroom.

And stops. Gapes.

Draped above him are wide panels of silky fabric—orange, bright pink, mustard yellow—lowering the ceiling by half. The tables, too, are skirted in these vibrant, familiar colours, and a trio of filigreed lanterns flickers over each. Bordering the dance floor are low couches of lush burgundy velvet, gold tassels on every pillow.

The expats call this “Bollywood”; they say it is a popular theme for Western parties. Still, it could not be more disorienting. This is no longer the ballroom, but the dancing hall of his mother’s dreams, set for the most extravagant birthday party his sisters could imagine. Surprise! He can almost hear their voices.

The most Pranav can reasonably expect for his birthday this year is a crackly phone call. The jumbled overlap of his nephews’ tender voices—Janmadin mubaarak ho ankal! Lambe jeevan, chaacha!—and then his eldest sister back on the line to whisper him an update on their mother. To ask when she should walk into town for the next wire transfer, because the hospital’s been calling again.But all these thoughts have made him late, and around him, several expat couples weave slowly through the maze of large, round tables, scanning the glittering gold placard for their number. Already an elderly couple has seated themselves in his section, and both have a drink in their hand; they’ve either stopped at the lounge off the lobby, or waved for one of the other staff to serve them. Pranav rushes to fill their water glasses, but there’s little else to do for them now. Grimly, he moves to his place against the wall and clasps his hands behind his back. Expats seating themselves? Not a good start to the evening.

Each of the tables are set for six, and on a good year, a full-section year, he’ll serve thirty expats. Having the correct drink ready at an elbow pays off at the end of the evening, but the expats like to drift. Rarely do they stay at their own tables, and it’s work to keep them straight. With every man in a tuxedo, this means paying attention to cuff links, or a certain style of watch, a snip of conversation overheard.

The women are trickier still. With them, you must watch without seeming to watch, and yet catalog every detail, because the expat females dress surprisingly alike. Year after year, they mince into the ballroom in dark, fitted gowns, their glossy hair pulled back or tucked away. Even their jewelry rarely distinguishes them: pearls or diamonds, diamonds or pearls. It’s as if they have a uniform of their own.

Disappointment flickers through him. A room like this should be filled with men and women in clothes as vibrant as the silks across the ceiling. He himself should be in a tailored sherwani—curry-coloured perhaps, the hem embroidered in emerald green. Certainly not this drab burgundy-on-burgundy, so much like the couches that if he sat on one, his torso would seem to dissolve right into the velvet. And the women! That is the greatest loss. His sisters and aunties and even some of the poorer girls from his village would arrive in their best: a rainbow of saris and salwar kameez, long hair swirling around their shoulders, stacks of bangles jangling on their arms. They wouldn’t dream of showing up in anything black or navy blue.

He won’t see a single soul who belongs in this room tonight.

Except one, perhaps. The woman with the mole. Married to the tall American with the onyx cuff links—a physician, if memory served. Neither of them remotely Indian-looking—and yet she had walked into this very ballroom, just last year, in delicate flat-soled sandals and an iridescent sari. Or not exactly a sari, but close enough that Pranav could imagine his father studying its cut and drape, the way the pale gold fabric shimmered over her curves. Yes, the physician’s wife stood out from the other expat women—and would have, he was sure, even without the mole.

It had been the very size and shade of a halved peppercorn, sitting just above the inside of one delicate eyebrow. She’d worn her dark hair swooped across her forehead, but even so the mole had peeked out from beneath. He remembers noticing it right away, and feeling surprised she’d never had it removed (certainly her husband could afford such things). Surprised…and oddly pleased. It looked almost like a bindi, gone charmingly astray.

Good for her, he remembers thinking.

Tonight, though, it’s only the husband he recognizes. A tall man, onyx cuff links, stride as arrogant as a leopard’s: yes, that is the physician. But who is the blonde woman clutching the physician’s elbow, wobbling toward his section? Has the man remarried? Brought a mistress? Where is the woman with the mole? Pranav smoothes down an unexpected twitch of something like loyalty. Because this new woman is taller. Thinner, too. Probably younger, though he can’t be sure. Expat wives of all ages have come through those double doors with puffy lips and a disconcertingly smooth brow. Certainly this woman’s breasts are artificial; they bulge at the top of her black velvet dress, straining the thinnest of straps. Platinum hair, twisted tightly at the nape of her neck, and yes—even in such low light, the enormous diamond studs at her earlobes flash. A smile which had seemed almost serene from a distance looks decidedly brittle up close. Now this one, Pranav thinks sourly, is made to order for the Charity Ball.

This spike of bitterness is alarming, unwelcome. Surely by now he’s learned what is—and is decidedly not—his business. He drops his gaze and steps forward to meet them at their table, murmuring a greeting, but she must have caught him staring. He can feel the weight of her gaze—and her hesitation, as if she’s debating whether or not to admonish him. Quickly, he pulls out her chair—and scrapes it across the physician’s shoe! Pranav tightens his grip, corrects just in time. He draws a deep breath, risks a glance up.

But the physician is still leaning across the table, kissing the cheek of a copper-haired woman, shaking her husband’s hand. His date has forgotten Pranav altogether. She’s directing that careful smile down at her lap, smoothing and re-smoothing the dinner napkin with the tips of her fingers.

He’s safe. No one has even noticed him.

Even so…when is the last time he’s fumbled, serving an expat? Another gaffe like that, and he’ll be the opposite of invisible. Already he can feel the sweat beading between his shoulder blades, gathering for the long roll down his back.

He’s moving away when the blonde stops him with a hand on his sleeve. Surprised, he glances down—and instinctively stiffens. A large diamond solitaire glints up at him through the lamplight. So it’s true then: the woman with the mole is gone, for good. The physician has remarried.

“Excuse me.” She glances at his nametag. “Could you bring me a drink, Pranav?”

He smiles down at her, his jaw tight. Every year you could count on it from a certain amount of expats, though usually it’s the men. Slapping you on the shoulder, slurring your name—even as their bleary eyes move across the nametag on your breast pocket. Man or woman, drunk or sober, yelling in your ear or tugging on your sleeve: inevitably, this kind of expat wants something. A stolen swig of the Consulate General’s $2,000 port or maybe a prostitute, an illegal fresh from the Eastern Bloc. Just as inevitably, this kind of expat forgets to tip you on the way out. As if the hotel paid you enough to take such risks.

“It doesn’t matter what it is, really. Whatever you think I’d like.”

“Certainly, madam. Right away, madam.”

What she wants, he has not figured out just yet. Exactly what she will ask of him, what risks she’ll expect him to take on her behalf—he doesn’t know this yet, either.

What he does know is the drink he’ll bring her. Since she asked for it.

Grown men, westerners and Arabs alike, have been known to stumble after one or two of Manish’s famous triple martinis. By the end of dinner—which she’d barely eaten—the physician’s new wife had ordered her third.

At each request, she’d laid a hand on Pranav’s sleeve and smiled up into his face. This was doubly irritating the second time…but disconcerting by the third.

So much alcohol, and yet she hasn’t done anything he expected. No giggling or guffawing, no spilling her drink or slipping off her chair—if anything, she’s grown quieter. He doesn’t know whether to have Manish make them stronger or water them down. He’d foreseen the physician’s elegant new wife losing all control by now. Embarrassing herself, and therefore—even better—humiliating the physician. Certainly, this man deserves it.

How could he give up that lovely woman in the sari?

Over the past few hours, fleeting moments—images, impressions—from last year’s Ball have come back to Pranav. The way she would reach up and tuck that swoop of hair behind her ear just before speaking, so that both her eyes—and the mole—became suddenly prominent. And that time, during some small exchange with Pranav during a loud song, when she’d leaned in to better hear him. Their faces had come so unexpectedly close he’d smelled lavender shampoo, and watched tiny wrinkles fan toward her temples as she smiled.

And then later, near the end of that exhausting night, he’d passed behind her chair and caught a sound that haunts him now. The slow tink-tink-tink of gold on glass: the inside of her wedding ring, tapped against the stem of a flute. A melancholy sound, so out of place he hadn’t recognized it then.

She had been unhappy that night, beneath it all. And so often alone, now that he thinks about it.

But even this new wife, with her expensive jewels and elegant dress, has failed to hold the attention of the physician. Plenty of male glances have been directed at the woman’s cleavage, but none from her own husband.

Half an hour ago, the physician had guided that redheaded woman out onto the crowded dance floor, his fingers steady on her bare shoulder. Pranav hasn’t seen them since.

Back at the table, the blonde suddenly drains her drink and pushes her chair back. She grips the table’s lip, testing her weight.

Once. Twice. Each time, she plops back down again, breasts bouncing. Each time, more eyes swing in her direction. Surely some other woman will help her to the ladies’ restroom? But no one moves, and she gathers herself to try again.

Pranav slips over to the table behind her and begins stacking his tray with half-empty glasses, his whole body tensed and ready. To do what? Catch her, in front of everyone? Bile rises in his throat.

Finally she stands on her own, steadies herself. She peers out over the dance floor and for one horrid moment, it looks as if she might move toward it, try to find her gaandu of a husband, maybe….

But no—she turns toward the double doors. Pranav exhales. The ladies’ restroom is only meters past the kitchen doors, down toward the lounge. Surely she will be fine…?

Waiting for her, he thinks of the mirrors. How disorienting they can be, really.

He collects a wineglass from one table, dessert plates from another. Each table a little closer to the double doors. He watches the other staff through lowered lashes; most he could call friends, but even so. Finally, with the fully loaded tray pressed to his stomach, he backs his own way through.

And—bhenchod!—nearly topples over her. Her bottom is propped against the mirror, and she’s bent forward at the waist. Both hands tug at the side of one shoe. Her breasts float between her forearms. He is close enough to see the freckles on her shoulder, the reddened skin where the strap bites into her flesh. She straightens and smiles at him, her pupils enormous. She struggles to focus them on his face.

“Varanasi,” she says. “In the northeast part. Right?” She squeezes her eyes shut and rocks sideways—he reaches for her upper arm, jerks back before he makes contact.

“Madam?” he says instead, but it comes out as a croak. His memory has stirred.

Now and then, a fresh-faced westerner will ask Pranav where he is from, where he calls home. Years ago, before he recognized these queries for what they were—his answer a mild, exotic thrill for the newly arrived—he’d given these little exchanges more weight than they deserved. Back then, that simple question could always deliver him, mysteriously, with all the power of an incantation, out of shadow and into light.

Back then, a question like that would make him feel…seen.

“It’s okay,” the woman slurs. “I’m sure, to you, we probably all look alike.” She closes her eyes, seems to be gathering herself. Her forehead wrinkles.

And he sees it. There. Above her eyebrow.

A tiny scar of pale and puckered skin, the ghost of a stitch.

Many months from now and an ocean from here, lying next to the stranger his sisters chose for him, Pranav will fall asleep and be back in this very moment. In his dream, he will reach up—brown palm to light cheek—and stroke this very scar with the soft pad of his thumb, and the physician’s wife will lean into the contact, eyes closed, lashes wet.

Many months from now and an ocean from here, he will wake from the dream to the worried eyes of his new wife, to the cool press of her small hands against his own damp cheeks. That new wife will slip her salty fingers in Pranav’s mouth, and draw his trembling chin to hers, and the month they spent as strangers will dissolve in a single night.

Now, though, under the harsh light of this hallway in the Gulf, with this tray of dirty glassware between them, he can only stare as this woman—the physician’s remarkable wife—turns and walks away.

Two men burst from the restroom then, drunk and laughing their way toward the ballroom. They pass the physician’s wife and leer back at her swaying bottom; one offers up a low whistle. If she hears, she gives no indication.

“Hey,” one of the men says darkly. “What’re you looking at?” And then a shoulder is in Pranav’s eye and he staggers backward, stars in his vision and the sharp sound of glassware against itself—he reaches out, blind, and traps two rolling flutes beneath his hand. The other expat sniggers and pulls his friend onward—a blast of music, and then silence—but still, it takes a moment to slow his heart. In that split second of eye contact before the shove, Pranav had caught the unmistakable menace, their possessiveness something primal. Don’t even think about it, brown man.

He ducks into the kitchen and sets the tray down beside the metal sink, begins unloading it himself. Hands shaking. One of the Ethiopian kitchen boys hurries over and pushes a clean tray into his side, shoos him angrily away, every gesture exaggerated under the supervisor’s gaze. Rami, from his cluttered, makeshift desk in the corner, says nothing—but Pranav knows better. The old Pakistani misses nothing. Pranav takes the new tray and heads toward the lounge.

The lounge is mostly empty, a few couples tucked in its deeper corners. Laughter—mostly male—booms in through the open French doors of the patio. Pranav gauges its timbre automatically, out of habit. The night hasn’t tipped yet; the alcohol is still at work in everyone’s favor. The expat’s thoughts of his consulate, his oil compound or barracks—all of these have been sufficiently diluted with Russian vodka and Canadian whiskey. They are coming up on the expat’s most generous hour.

Waiting on the bar is a full tray of shots—expensive imported tequila, set aside for Pranav. He orders a dozen tumblers of plain water instead, ignores Manish’s sideways glance. He keeps picturing the physician’s wife in a bathroom stall, knees bony on the tile, retching into the toilet. It’s left him suddenly exhausted. Probably right now the other wives, remembering their husbands’ eyes on her breasts, are clicking past that stall in their expensive shoes, reveling in the sounds of her sickness. Karma, they’re probably thinking, happy to bring news of her disgrace back to the ballroom.

From the corner of his eye, Pranav sees a familiar man slip into the lounge, alone, from the hotel lobby. The physician. He scans the room and heads casually toward the ballroom.

Pranav hopes that his wife is still in the ladies’ room, on her knees—better that humiliation than to see her husband stride down the hall, an onyx cuff link missing. Better to stare at the bathroom tile than to come face-to-face with the redheaded woman, who steps into the lounge a few minutes later, hair freshly gathered but her dress now creased. The redhead glances toward the ballroom, but crosses instead to the patio and steps out. Pranav picks up his tray of tumblers of water and follows.

He’s halfway through the French doors when someone tries to brush past him, someone who trips on the doors’ lip and almost goes down. It’s the physician’s wife, not in the bathroom after all—and though she catches herself, straightens up before the fall, it is no victory.

One of the dress’s thin black straps has finally given out. It hangs limp down the front of her, and Pranav stares in horror and helpless wonder as the cup of her dress peels down along with it. The areola appears slowly, a dark half moon rising, smooth and surprisingly large. The nipple is tight and dimpled. Pranav looks over at the bar, desperate, and sees his shock reflected in Manish’s face.

But the physician’s wife doesn’t gasp, or seem to even notice her exposure. Her eyes sweep through the lounge like a hawk’s on the hunt. She steps around Pranav and moves swiftly toward the doors to the mirrored hall, the breast now completely exposed.

Pranav swallows, deciding.

By the time he fumbles his tray down to the carpet and bursts through the swinging doors, she is halfway down the hall.

“Madam!” he yelps. “Madam, please!” The funny note of desperation in his voice startles him and stops her. She turns. The dress is completely lopsided by now, the strap twisting in the air. He trots toward her, fishing around in his left pocket—the sticks of gum, the aspirin…there! His fingers close over a tiny sewing kit. He’s carried it for every Charity Ball now, since the year his pant leg’s hem came apart. He’d spent the evening tucking one leg behind the other like a man indisposed, imagining his father’s cluck of consternation in one ear. Two years ago, with the same kit he jerks from his pocket to wave at her now, he’d stitched a giant tear in Manish’s elbow, right there behind the bar. At the end of that night, Manish gave him one hundred riyals out of his own tips, nearly a week’s worth of regular wages.

The physician’s wife turns and waits now, squinting at the tiny sewing kit, at Pranav’s imploring expression and his other hand, gesturing where his eyes dare not go. Finally, she drops her chin down to her chest and—far from clutching her breast or jerking her dress up or, at the very least, turning away from the dark-skinned man bearing down on her—she laughs. Once: short and bitter.

“Well. He did pay for them. I guess he should get a good look at what he paid for, shouldn’t he?” And she turns again toward the ballroom, but by now Pranav is there and before he has time to think better of it he claps a hand on her shoulder, begs, “Stop!”

She stops. His hand drops away. A sound from the kitchen fills the silence: a pot lid hitting the tile, its metallic rim rolling tighter and tighter, until someone clamps it flat with a foot.

“Please,” he whispers, out of breath, “I can help. Please.” He pops open the kit and quickly, hands trembling, plucks out the needle and the little loop of black thread. He holds them up and looks into her face and smiles tightly, eyes begging her to trust him or to laugh in his face, but either way to hurry. He cannot believe his own nerve. He doesn’t know how long he can hold it.

She closes her eyes and shakes her head once, slowly…but then swivels where she stands, close to the mirror. She puts both hands to the top of her dress and yanks it up, with such tense, clutching force that she loses her balance and slaps one palm against the mirror to steady herself. With the other, she gropes at the fallen strap and flips it over her shoulder, back toward him. He can feel her eyes on him in the mirror, but trains his own on the half-inch of fabric, his heart beating hurry-hurry-hurry. He knows how this looks. Already, though, he is a fool.

He picks up the strap between thumb and forefinger, trying not to touch her skin, even as he sees that will be impossible. The seam has given out, but that’s all; good news, but he will need to put his hand down the back of her dress, just a little under the shoulder blade, so that he doesn’t prick her.

“Madam?” He flicks his eyes to the mirror, meets hers. “It is okay?” He makes a motion to show her what he means. She nods, eyes welling now. He looks away, at the fabric. Hears his father’s whispered guidance—backstitch only, there and there, reinforce it—and then his fingers slide down the soft skin of her back to meet the needle.

At this contact, something seems to break in her. Her body begins to heave, silently at first…but soon the sobs are great, gulping cries.

In each one, whole years of loneliness. His vision blurs; he swipes at his eyes. I see you, he wants to tell her. You are not invisible.

Behind them, a kitchen door creaks on its hinges. He blocks it all out: the sting of his own tears, the smell of a woman’s flesh, the weight of accusing eyes. Everything but the in-through-loop, in-through-loop in front of him. After a long moment, the kitchen door swings shut and they are alone again with the sound of her sobs. He tries to find a rhythm, to work in time with the heave of her shoulders. His fingers shake.

Ten seconds later, the doors burst open—Rami this time, horror in every syllable.

“Madam! Pranav! Madam, I am so—”

“GO,” she booms, her voice so guttural Pranav’s hand jerks under the fabric.

Years from now and miles from here, crouched on a bench repairing his son’s school uniform, he will prick himself and remember tonight, this very moment. He will wonder about this other drop of blood, so long ago, whether it had smeared into the fabric of the dress or tattooed itself on her back.

But now he finishes quickly, with the sharp teeth knot and flourish of his father, and whirls around.

The kitchen door still swings, but Rami is gone, of course… and with him Pranav’s tips, his position, and probably his visa. He draws a deep, shuddering breath and turns back to her. In the mirror’s reflection, his eyes meet hers.

She has quieted herself and watches him now. She looks awful, cheeks streaked in dark rivulets, lipstick smudged, nose pink and raw—she wipes it with the back of her hand like a child, eyes on his face. Contemplating something. Contemplating him.

Abruptly, she turns from the mirror to face him and Pranav takes a step back. A reflex, still.

“You’re going to get fired, aren’t you.” It’s not a question. They both know the answer.

He shrugs and drops his eyes, trains them on the strap instead. Strong once again. His father would be proud.

She steps forward and in an instant he is trapped, her thin arms wrapped around him. Shock ricochets through him. Warm breath in his ear, a quiet thank you, the fumbling of hands behind his back and the smell of lavender and then he’s squirming away when—just as quickly—she releases him and steps back. He can’t speak, can’t move.

She lets out a shaky sigh, looks toward the ballroom doors. He registers the relentless, muffled thump of the bass, but it sounds kilometres away.

She smiles and bends sideways, steadier this time. Pulls off one terrible shoe, then the other. Immediately, astonishingly, they are eye to eye. She is the size of his sisters, his mother and aunts. She chuckles at his expression. She tells him she is going home.

“You should too,” she says, over her shoulder. She’s headed toward the lounge, the lobby, and beyond that, the line of taxis waiting just outside.

Later, emptying the pockets of his uniform for the last time, after his fingers close around the sticks of gum, the aspirin, the sewing kit, the tips—not as good as last year’s, though it’s no wonder why—he will find the ring. The diamond, as big as the mole she’d had removed. He will gasp, flush, think immediately of how to return it. He’ll leap up, sit down, leap up again. Pace for a while. He is thirty today. Eventually, he’ll open his fingers and let the hard little object settle in the pocket of his own slacks.

*****

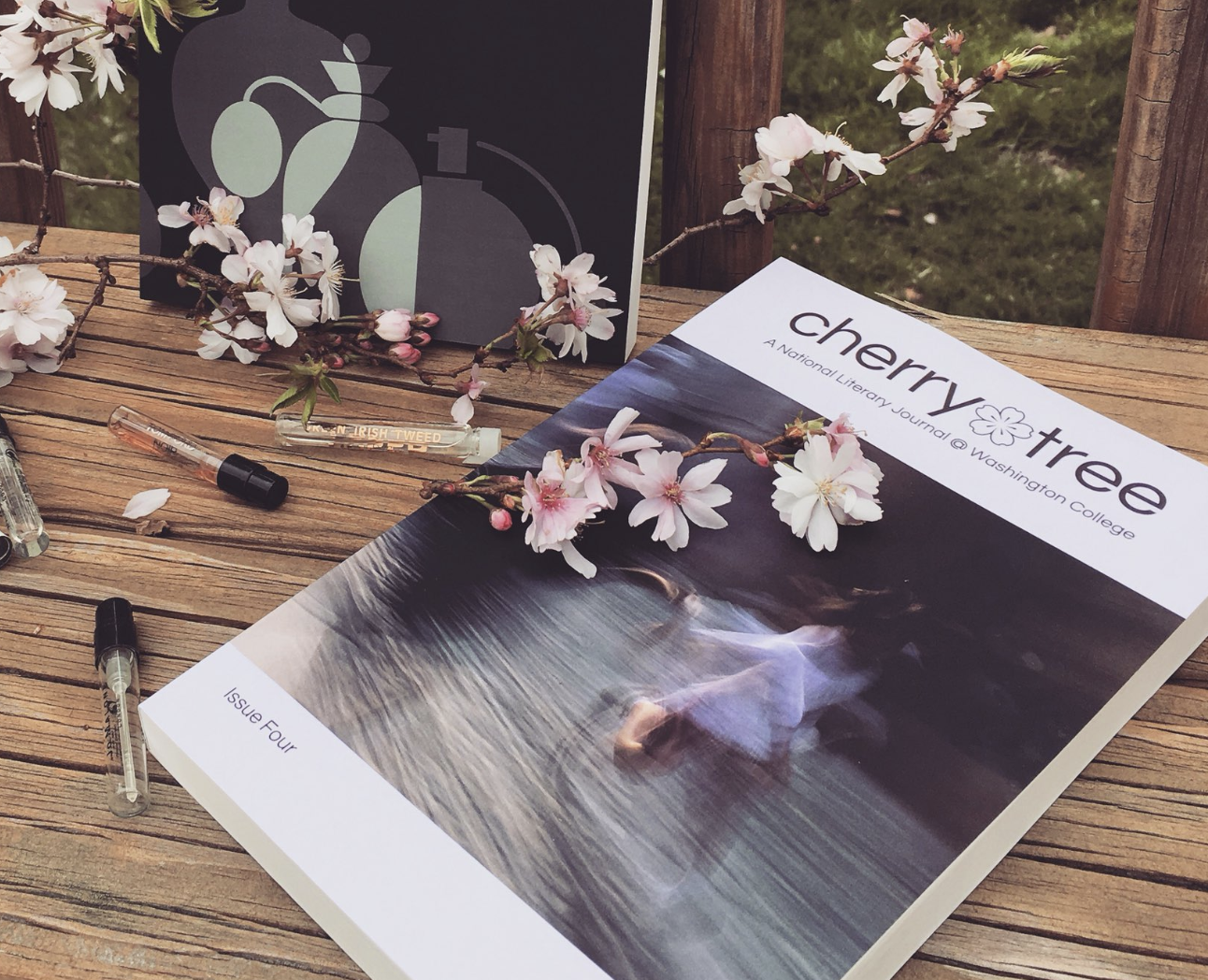

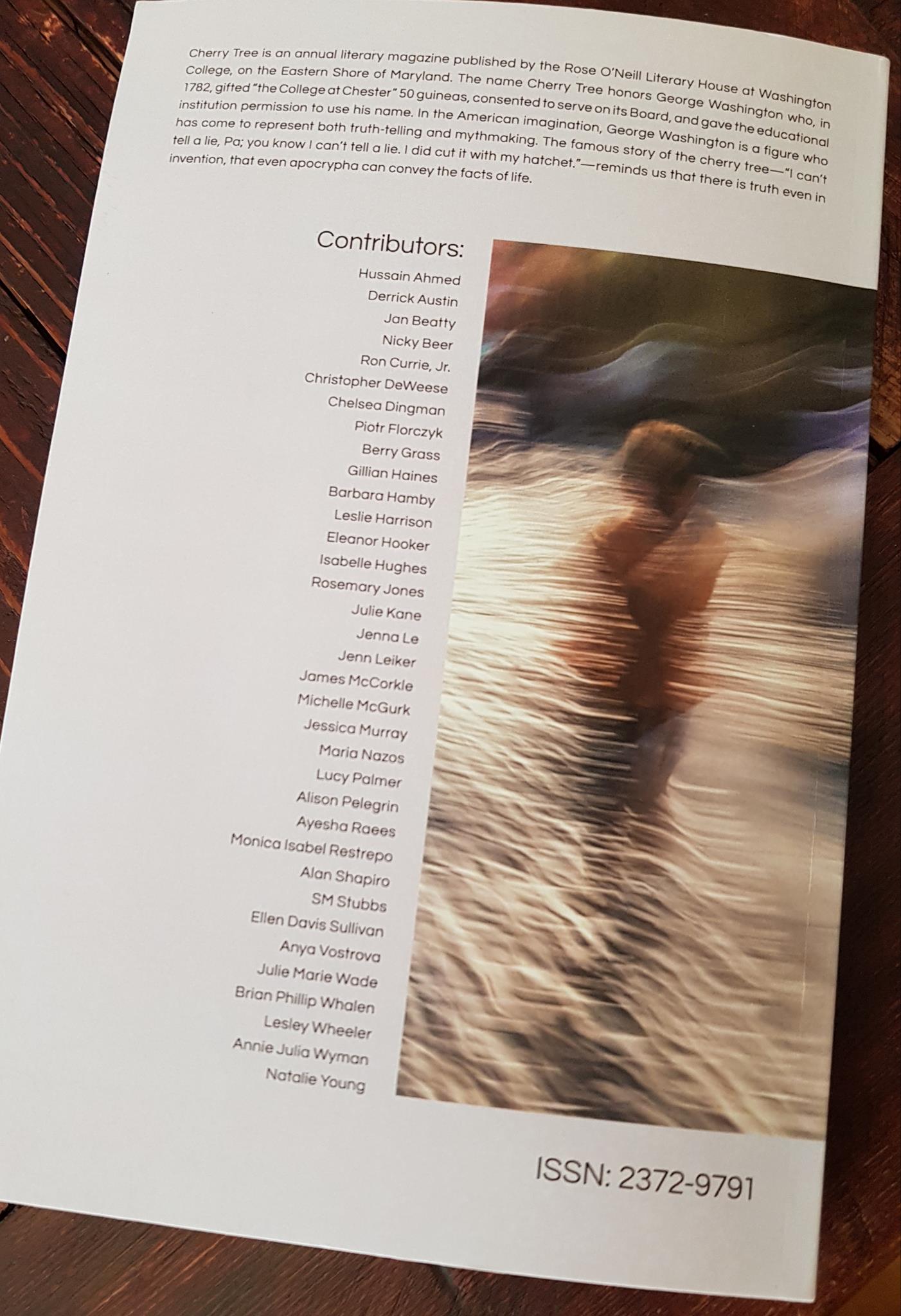

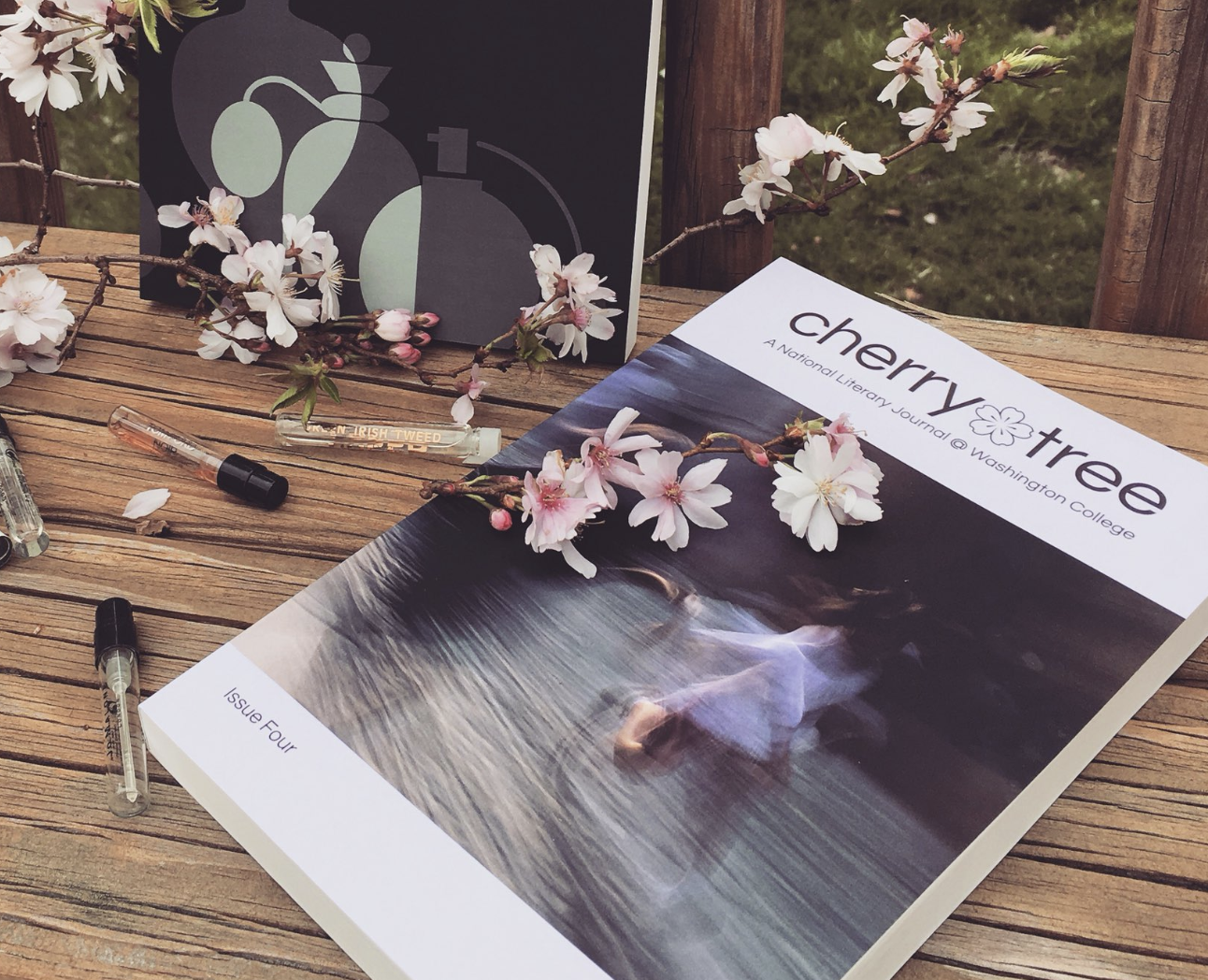

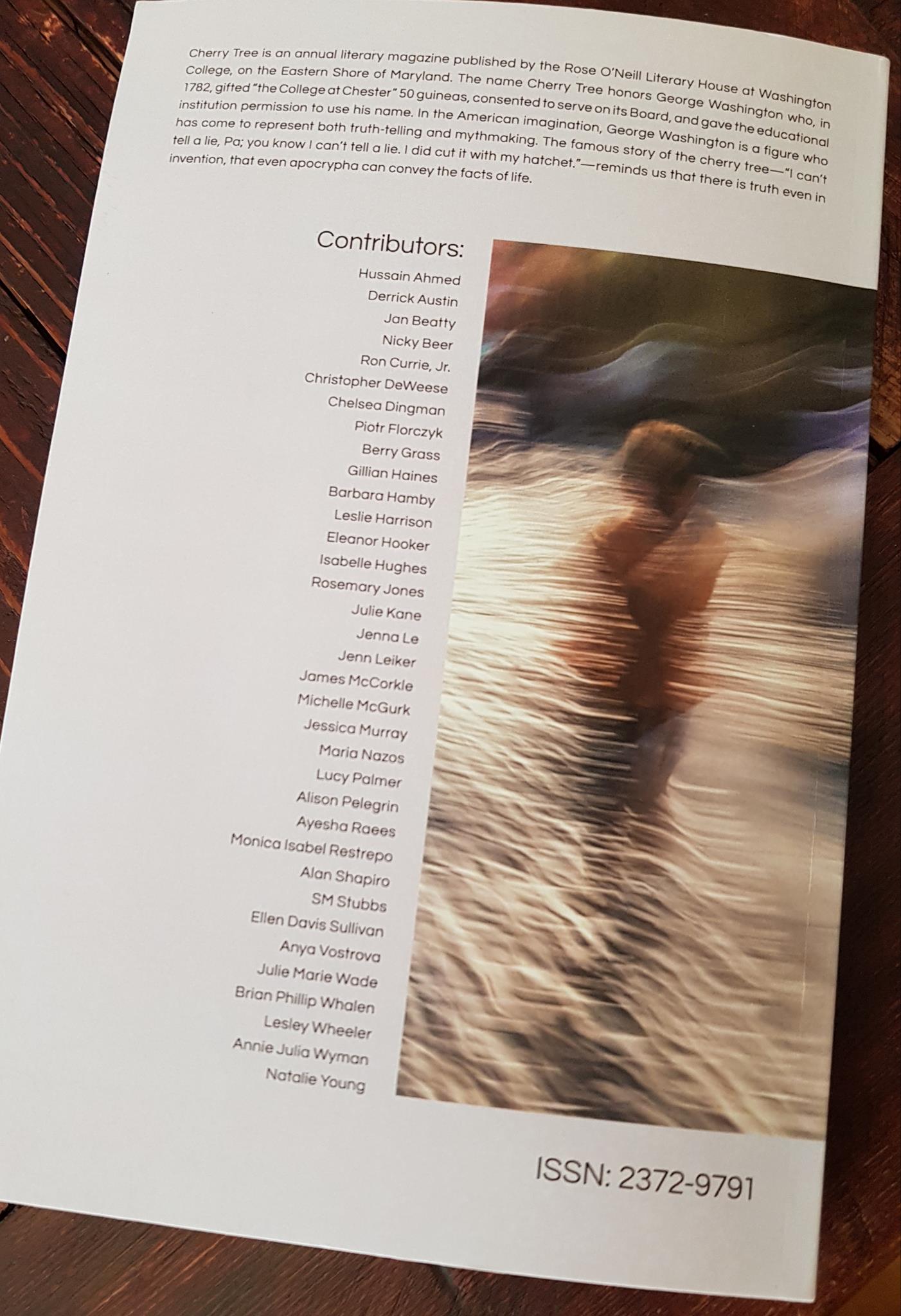

“Stitched” first appeared in Cherry Tree: A National Literary Journal @ Washington College (Issue 4), 2018.

“Stitched” first appeared in Cherry Tree: A National Literary Journal @ Washington College (Issue 4), 2018.

“Stitched” was also honoured with a spot in Cherry Tree’s Literary Shade section. Here’s a word on how the editors choose these featured pieces:

“In the great tradition of Jennie Livingston’s documentary, Paris is Burning, we aim to publish impeccably-crafted shade. But not just ordinary shade: poems, short stories, or nonfiction that throws shade at the institutions that have whitewashed our literature and history, be they laws or events or texts authored by cisgendered white supremacist misogynistic homophobes. We believe that shade—subversive wit, withering critique—can empower. And there is a lot of shade under the cherry tree.”

A big thank you to managing editor Lindsay Lusby, who was just a delight to work with. I’m so pleased and proud to be a Cherry Tree contributor. It’s a beautiful annual full of fabulous fiction, nonfiction, and poetry, and you can subscribe here. Remember to follow Cherry Tree’s Twitter and Facebook feeds for more literary goodness.

A big thank you to managing editor Lindsay Lusby, who was just a delight to work with. I’m so pleased and proud to be a Cherry Tree contributor. It’s a beautiful annual full of fabulous fiction, nonfiction, and poetry, and you can subscribe here. Remember to follow Cherry Tree’s Twitter and Facebook feeds for more literary goodness.

If you liked reading this story, please consider “sharing” it with your friends through the links below, or along the side. It’d mean a lot!

Thanks for reading along,

Jenn

“Stitched” first appeared in Cherry Tree: A National Literary Journal @ Washington College (Issue 4), 2018.

“Stitched” first appeared in Cherry Tree: A National Literary Journal @ Washington College (Issue 4), 2018. A big thank you to managing editor Lindsay Lusby, who was just a delight to work with. I’m so pleased and proud to be a Cherry Tree contributor. It’s a beautiful annual full of fabulous fiction, nonfiction, and poetry, and you can subscribe here. Remember to follow Cherry Tree’s Twitter and Facebook feeds for more literary goodness.

A big thank you to managing editor Lindsay Lusby, who was just a delight to work with. I’m so pleased and proud to be a Cherry Tree contributor. It’s a beautiful annual full of fabulous fiction, nonfiction, and poetry, and you can subscribe here. Remember to follow Cherry Tree’s Twitter and Facebook feeds for more literary goodness.

Be First to Comment